Boresha Elimu Campaign: Bringing 1,200 children back to school in Ngong’, Kenya in 2014 (Case study)

Haruka Sano, Jacob Okumu-

Type

Case studies

-

Region

Africa

-

Practice

Coaching, Public narrative, Relationship building, Team structure, Strategy, Action

-

Language

English

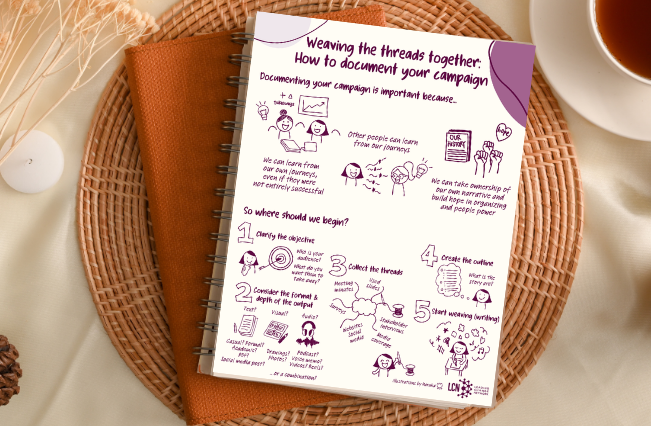

This campaign documentation is a reflective piece that highlights the steps, the challenges, the impact, and key learnings of the Boresha Elimu Campaign. This document aims to provide insights into the application, adaptation and learning of community organizing in the East African context.

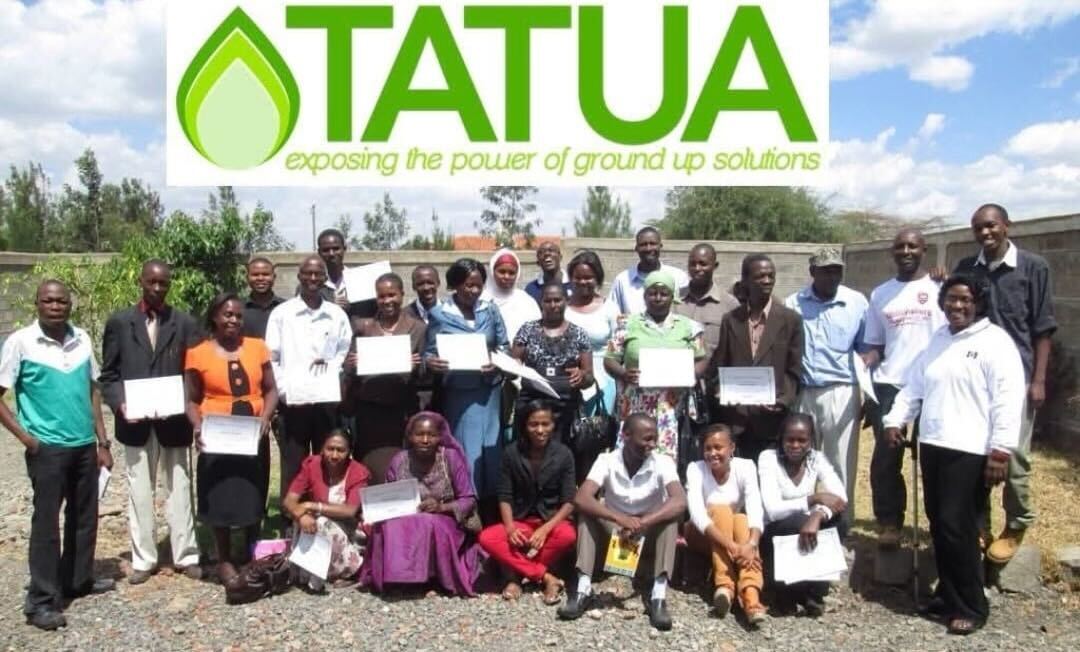

About Tatua Kenya

Tatua is a community organizing institute, founded in 2010, that trains, coaches and models community organizing practices in East Africa. The program targeted activists, grassroots community leaders, community-based organizations, NGOs, and international organizations. Read more: https://tatuakenya.wordpress.com/about/

About Ngong’, Kenya

Ngong’ is a bustling, cosmopolitan region on the outskirts of Nairobi, home to an estimated 102,000 people. Over the years, it has grown into a melting pot where different communities, ethnic groups, and faiths meet and coexist, each contributing to the area’s unique character.

The community is made up of three main neighborhoods or regions, each with its own story. Ngong’ Town, once known mostly as an administrative centre, has transformed into a lively middle-class hub, with businesses sprouting up and young families settling in. Bulbul, by contrast, leans more towards an informal settlement, where residents often grapple with challenges like unreliable water supply and poor sewerage, yet it remains full of energy and resilience. Further out lies Matasia, which still carries the feel of a rural setting, with spacious homesteads, farms, and a quieter pace of life.

Together, these regions paint a picture of sharp contrasts—between wealth and struggle, modern and rural. Yet despite these differences, Ngong’ has managed to hold onto something precious: a spirit of coexistence. People from all walks of life, with diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds, have found a way to live side by side, shaping Ngong’ into a community that is as complex as it is vibrant.

Who were our people and what was our problem?

In 2013, being a cosmopolitan town that was growing rapidly, Ngong’ manifested many challenges, especially related to safety and the well-being of the children. Child poverty was rampant in this community, quite evident by the sight of street children in Ngong’ centre, participating in child labor; many children walking around carrying big sacks of scrap metals and broken plastics during school hours in Ngong’ centre and Bulbul town. Walking through the neighbourhoods of Ngong’, you would notice teenagers hanging out in “squads,” chewing khat, and playing poker for the better part of the day. As a result, it was reported that insecurity had risen to an alarming height.

The members of the community, for a very long time, had resigned themselves to the belief that they had no solution to the challenges they were facing and that they had to largely depend on the support from the external development partners to fix their problems. This belief and thought process were conspicuously visible from the onset, as evidenced by the responses we got when the issue of child poverty came up. Comments like, “Yes, this can be done, but only if donors, or the government, help us,” were common. Rarely would we hear people affirm their power to bring about change through collaboration and community’s resourcefulness.

While the donor culture had delivered great results in tackling child poverty, many questions still lingered in our minds as we worked in the communities of Ngong’, Bulbul, and Matasia. Children were still out of school, roaming the streets, and selling scrap metals. We still had children going to school hungry and many dying from treatable diseases. Despite the many NGOs that were working in these communities, child poverty was still rampant. The bigger question in our minds was “To tackle this menace, should donor funding in these communities be increased, and if so, until when?”

Stage 1: Understanding the problem and raising awareness through a listening exercise (February-March 2014)

At the beginning of the campaign, we, the Tatua Kenya-trained community organizers, conducted a listening exercise to really listen and learn from the perspectives of those most affected by the problem we were seeking to address. We held over 60 one-on-one conversations, and 12 focus group meetings of at least 15 people each for five weeks, and gathered the community’s feelings, thoughts, and opinions on child poverty and what change looks like to them. We gained a deeper understanding of the community and the challenge, getting information about child poverty from the community’s perspective.

Before the listening exercise, we mapped out the stakeholders that we should talk to in order to get a better understanding of the community, the challenge, and what the change should look like. The stakeholders we mapped out were as follows; the constituency (the most affected by the challenge we were seeking to address): parents and children who were affected within Ngong’ community, parents and guardians whose children had dropped out of school, parents and guardians who had their children in the streets, guardians taking care of orphans, grandparents watching children left by parents working in other towns, parents and guardians of victims of child labor, the school community, and the children homes; the leadership: leaders from the constituency; the supporters: the local arm of the national government, the ministry of education, the county government, civil society organizations working with children, the church community, the business community; the oppositions: scrap metal owners and business community exploiting children; others (this group was not directly involved in the campaign but had the potential to influence the campaign positively or negatively depending on how we would engage them): lawyers, journalists, professional networks within the Ngong’ community, and mediators. Our main focus was on the constituency because we strongly believed that until the constituency rises to tackle its own challenge, the problem would not be solved sustainably.

As the listening exercise reports streamed in, we started to notice a trend: a huge lack of trust in the public amenities in Ngong’, especially in the public schools and hospital services.From all corners, you could hear the lamentation of the government having failed to establish a clear channel of directing resources to the grassroots. A lot of bureaucracy, intermediaries, and complex procedures had barred the communities, especially the youths, from accessing these services. While the government pointed to a few schemes like Youth Funds, Uwezo Funds targeting women entrepreneurs, and Constituency Development Fund, as efforts made towards alleviating poverty, it still retained the lion’s share of blame for misdirecting these resources. The community pointed out the fact that these funds did not benefit the intended persons, due to the intense competition, bureaucracy, and corruption. These resources, unfortunately, still ended up in the hands of the few able and connected.

The listening exercise reports also noted that though the community appreciated the work the NGOs were doing, their impact had reduced the community to passive beneficiaries who felt that they could not make any meaningful contribution to the efforts of finding solutions for child poverty in their community. This had embedded in them self-doubt and perpetuated the notion that the outsiders know the best, hence they just have to wait for them to come and fix their challenge.

In addition to the blame that the government and NGOs were receiving, we also noticed that the parents too had a part to play in the problem. While in the rat race to fend for their families, they seemed to have gotten so overwhelmed by the demands of life, so much that parents unintentionally neglected their roles as parents, such as spending time with their children and talking about issues that affected them. There was a general sense that parents had to change how they relate to their children and those under their care. This insight was very instrumental in helping us arrive at the theory of change.

Through the listening exercise, the community began to understand that the current situation that they have resigned to is far from ideal and isn’t acceptable. Their apathy began to transform into anger for change, and their inertia transformed into a sense of urgency. Through our continuous practice of community organizing skills in the listening exercise, more than 200 community members learned about the campaign.

Stage 2: Committing to pursuing change at the community info session (April 2014)

With the bulk of information from the listening exercise, we were ready to face the community and present to them our findings through a community info session. One afternoon in April, we invited the community to understand the issue from their own eyes. We brought together 46 people from all three regions, Ngong’ Town, Bulbul, and Matasia, in one room, because we wanted them to see the differences between the three regions and understand why the regions need to be distinguished.

We discussed how to move forward–confront what would happen if we acted, and what would happen if we didn’t. The objective of this info session was to have leaders step up and commit to organizing the community. At the end, the community elected a leadership team of 16, each of whom were willing to serve and were able to articulate how they would help the campaign achieve its goal. Considering that the campaign covered three regions, we ensured that all three regions were represented in the leadership team. Others outside this leadership team also committed to be a part of the campaign, to develop the strategy together, and to take action together. They committed to pursuing change together as a community with a shared challenge.

Stage 3: Training the team at the community organizing workshop (May 2014)

The 16 leaders got trained at a three-day community organizing workshop in the beginning of May. The training included public narrative, relationship building, team structure, strategy, and action. We monitored and coached them all through the training so that they can develop their capacity to lead the campaign.

The 16 leaders were also segmented into four committees. The Team Relations and Growth Committee was in charge of training and coaching the team. Their main responsibility was to identify the capacity gaps in the team and organize training around that for the team. The Resource Mobilization Committee was in charge of mobilizing resources both internally and externally. The Strategy Committee was in charge of organizing the cells around strategy (The cells will be explained in Stage 5). They were also in charge of keeping the cells focused on their plans. Additionally, the Community Liaison and Event Management Committee was responsible for coordinating the event and outreach program. We deliberately ensured that these committees were interdependent. The success of each of the committees hugely depended on the success of other committees. These roles were reflected at the community cell levels.

We trained and engaged new leaders, as the campaign process continued and more leaders emerged. Training and coaching were deliberate and continuous all throughout the campaign. We would identify a capacity need, conduct a spot training targeting the leaders, and support them as they cascaded down the training to the field.

Stage 4: Building the theory of change at the collective decision-making and strategy development session (June 2014)

At this stage, the community was already getting stirred up; they had already understood that something needed to change. In the one-on-one’s in the earlier stage, we heard about their isolation, fear of being targeted, and lack of confidence: “We are not educated. We are not donors.” So by bringing them together, we created a sense of security: “Oh we are many! Let’s do this now!” Their fear was becoming replaced with hope for a better future. The campaign began to take shape, and it was important for us to manage the already boiling energy and anger for change.

Through in-school and out-of-school events and community meetings, we created a platform for them to build relationships with each other, organize themselves in teams, and strategize in their regional community cells. Our objectives during this stage were to strengthen the constituency, to train the community leaders on community organizing skills, to narrow down to one challenge, and to draw a clear strategy with a small goal and a clear path with timelines.

We held a collective decision-making and strategy development session, where 76 members of the community came together. Understanding the complexity of the issue, how they were interrelated, and the fact that we could not address everything at once, we agreed to settle on a goal that could address as many of the symptoms and root causes as possible. Through the problem tree analysis, we concluded that enrolling and keeping children in school would keep them safely protected from child poverty-related issues. And for this to work out, parents and guardians needed to understand the value of education and talk to their children, so the children would, in turn, agree to go back and stay in school.

Hence, our theory of change was “If parents and guardians understand the value of education, they will engage with their children and the children will return and stay in school.” Eventually, this theory of change inspired the campaign goal of getting 1,200 children to commit to going to school consistently and productively within a period of six months.

In building the theory of change, the community examined their resources, such as time, money, skills, relationships, and materials such as books and pens for children, and spaces and tea for holding meetings, sometimes offered by grocery vendors and churches. Some community members were able to drive the leaders from schools to Tatua’s training venues. People were feeling inspired by these contributions from the community and their own resourcefulness.

Stage 5: Mobilizing our people in collective action through a solid structure (July-August 2014)

A good plan without action is but wishful thinking. The team clearly understood that any meaningful change would only result from consistent action as guided by our collective strategy document. As the strategy became alive through meaningful actions by the community, the community that initially felt isolated started to feel solidarity.

A cell was a group of parents who got together every week or every two weeks to discuss the importance of education and their role in supporting the education of the children in the community. Each cell would be in different streets and different areas even within Bulbul for example, so that parents did not have to walk long distances to attend the cell meeting.

In order to hold each cell accountable, there were accountability buddies, strict norms, norm correction, and clear roles. Each cell had 1-2 cell leaders, a team relations lead, and data management lead (someone who evaluates and reports back on how we are doing). Each cell also has the commitment book, which records who is engaged how much–how many cell members were engaged and how many children were committing to go to school.

There was a bit of resistance to structure in the beginning. For example, cell members asked, “Who’s the chairperson? Who’s the secretary?” So during our meetings, we expanded their role and breathed life into their roles by calling the chairperson and secretary, “team leader” and “team relations person.” When designing roles in organizing, we design from what we need to achieve, and what responsibilities are needed.

Each cell comprised 10 cell members including cell leaders, and each of the three regions, Ngong’ Town, Bulbul, and Matasia, had 10 cells, which meant a total of 30 cells and 300 cell members across the campaign. The cells held regular cell meetings. Each of the cells held 8 children’s forums to identify children who are not committed to going to school consistently and productively.

In addition to the regular cell meetings, the community started programs at school to appreciate teachers, donating materials and holding regular events for the children under the program. They also volunteered to rehabilitate part of the schools infrastructure that were dilapidated. Parents went to the children’s schools, helping, gardening, and cleaning classrooms together with the students that they were mentoring.

The campaign team composition was inspired and guided by the snowflake structure. It was important for us to organize our leadership, which was to facilitate team growth and collaboration. This structure also made communication and coordination more efficient and faster. The cell members knew each other and their stories; with this structure, we were more in touch and even able to identify if any of the members was struggling.

Taking rest and reflecting at every stage

After every campaign stage, it’s important to lead the teams through a rest and reflection time before they start the next stage of the campaign. Coaches must take deliberate efforts to manage the energy and excitement of the campaign team as the campaign progresses through different campaign peaks. After achieving every campaign peak, the strategy team deliberately ensured that the cell members took time off to rest and meet to reflect, retrain, and reenergize.

We learned that, although the cell members are usually excited to keep going after achieving a campaign peak, most often this is false energy. As a leader, you risk the team getting fatigued when the campaign really needs them the most. Strategic rest and reflections are key in organizing campaigns.

What changed as a result of the campaign?

A total of 529 people, including the 300 cell members, partners, and other stakeholders with an interest in education, attended community forums and learned about the campaign. 1,200 children were identified from all three regions of Ngong’ Town, Bulbul, and Matasia, all received mentors, and by the end of August 2015, signed commitment forms to enroll and stay in school, through their regional community cells.

At the end of the campaign, we developed 9 strong leaders (Some of the 16 leaders dropped out and 9 remained) and trained an additional 30 cell leaders. A local advisory network was set up, consisting of professionals in the community to support, especially on leadership coaching and building resourceful networks to support the campaign with further mobilization of these resources.

We were working with a community that is used to handouts and the culture of development, so it was challenging to say, “This is your responsibility and we will not pay you. In fact, we want you to start figuring out the resources you can bring to the campaign.” We had to do a lot of listening and relationship building through one-on-one conversations, for people to start contributing resources. It was important to recognize small wins such as “Look at how many people you brought,” “Look at how you shifted the conversation,” and “If you were able to do this much, what can we do?” We kept people motivated not only by training and coaching, but also showing them how they were growing as individuals; growth looks different for everyone.

At the beginning, Tatua had to organize meetings–find a place to meet, send reminders. However, toward the end of the campaign, we were the guests in the campaign, getting invited to committee meetings. It was because we wanted to delegate power as much as possible, and constantly communicated to them that this was their community, and that if someone were to fix it, it would be them.

We witnessed the community begin to take initiatives and leadership roles, and make donations towards the campaign. We also held numerous community meetings that brought together a total of 529 people without paying them any allowances, 300 of whom volunteered to mentor four children each. We had a total of 1,200 children committing to completing their primary school, and we were able to start a feeding program in Enomatasia Primary School. The bigger change was the community shift in attitude towards taking responsibility in bettering the quality of education in the public schools within these communities. Different stakeholders who initially had a challenge working together ended up collaborating and beginning to imagine a bigger picture for the campaign and a brighter future for their community.

Down the line, the campaign metamorphosed into demands for another learning institution that can ensure that the children in the Ngong’ community would get access to quality education for a long time. The community noticed another problem of overcrowded classrooms, and started talking with the Ministry of Education so that the government would commission a school. This was possible because we left a community that was able to start thinking for themselves, by themselves.

About the author

Jacob Okumu, based in Kenya, is a teacher by experience, a project manager and a community organizer with knowledge and experience in training, coaching, designing, and managing people centric projects/campaigns for social change. He is a supporting coordinator at Global Grassroots Support Network. He has led and managed campaigns and projects with organizations such as Be the Change Kenya, Tatua Kenya, Amnesty International Kenya, UNICEF Tanzania and Change.Org where he has been infusing digital and offline campaign strategies to enable petitioners and Change Leaders accelerate change as a campaign strategist. He is a member of the Young African Leadership Institute (YALI) Alumni, and Leading Change Network. He is passionate about justice and equality.

Resource Information

- Year: 2025

- Author: Haruka Sano, Jacob Okumu

- Tags: —

- Access : Public

- Topics : Education

- Regions : Africa

Back to search results

Back to search results