How to Document Your Campaign Session Write-up

Antje Dun, Haruka Sano-

Type

Articles

-

Region

Global

-

Practice

Coaching, Public narrative, Relationship building, Team structure, Strategy, Action

-

Language

English

Introduction

On September 30th 2025, around 70 participants from around the world gathered for Weaving the Threads Together: How to Document Your Campaign session, hosted by the Commons Social Change Library and the Leading Change Network. The session was framed not as a one-time event but a start of an ongoing conversation for participants to discuss documentation practices and actually document campaigns.

Why is it important to document our campaigns?

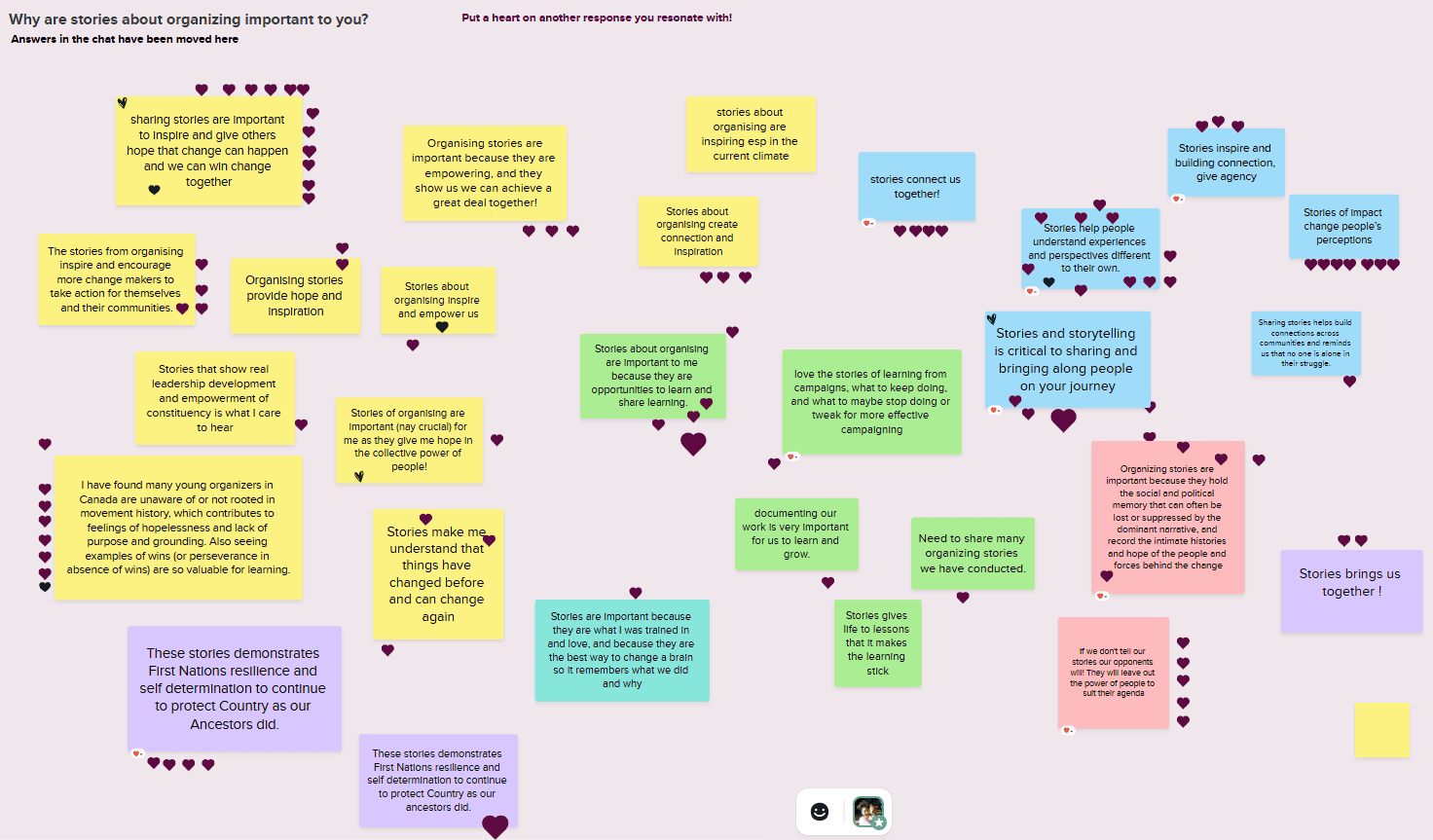

First, we discussed why it is important to document our campaigns, building on our check-in question: Why are stories about organizing important to you? The most frequently used key word here was “inspiration”–the idea that sharing stories of organizing can give others hope that change is possible, and encourage others to take action for themselves and their communities. (See the yellow post-it responses in the Mural screenshot.) There were also ideas shared around stories connecting and deepening understanding among people, and around stories helping our learning and growth.

Why is it difficult to do?

Having understood how important we think documentation is, we moved on to the difficult question: If we think documentation is so important, why do we not do it all the time? What gets in the way of our documenting our campaigns?

We categorized our challenges into head, heart, and hands. The head challenge is strategic; for example, we are often not sure what goal to set or how to get to that goal. The heart challenge is emotional; even if we have a goal and know how to get there, sometimes we lack motivation or confidence to take action. The hands challenge is skill-based; despite having a plan and feeling motivated, we often just don’t have the tools, skills, or time to implement it.

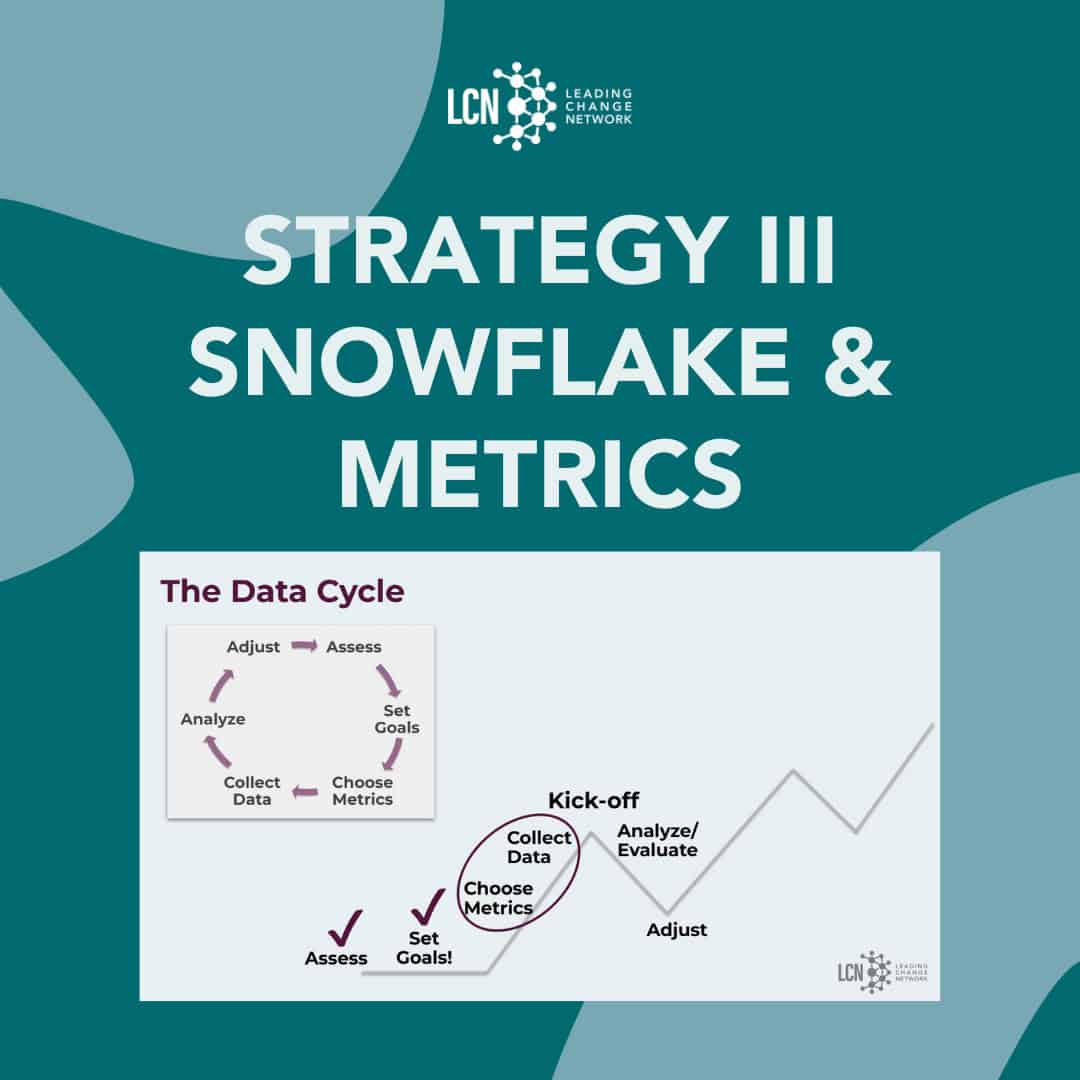

One of the head challenges that stood out was the difficulty of measuring the impact of the campaign that is not just the simple winning or not winning the campaign. In addition to the societal impact of achieving the goal, we value two other outcomes in organizing: the organizational growth and individual growth. In other words, it is important to measure the organizational capacity and individual leadership development through the campaign–but how can we measure that?

Regarding the heart challenges, many participants resonated around thinking their own campaign is not significant enough to document. This may especially be true if the campaign did not have an obvious success in terms of societal impact, which connects back to the head challenge of not knowing how to evaluate other aspects of success–organizational capacity and individual leadership development.

Finally, the lack of time was mentioned by various participants as a hands challenge. It seems that documentation is often not embedded in the organizing culture by default, and thus there is no designation of archivist role or meeting time intentionally dedicated to documentation.

How to document our campaigns

This part of the session delved into how different organisers and organisations document their campaigns.

Commons Library

Holly Hammond from the Commons Social Change Library shared different examples of how campaigns can be documented, including:

- A structured academic case study of the Stop Adani climate campaign, detailing targets, tactics, and networks.

- A storytelling approach from Original Power’s Building Power Manual, sharing the Gurindji land rights struggle alongside music and group discussion.

- An oral history project on a wage theft campaign by Ian McIntyre, complemented by a shorter zine summarising key lessons.

- The Commons Conversations Podcast, which records in-depth interviews—such as one between Tarneen Onus Brown and Noora Mansour on First Nations and Palestinian solidarity—to capture campaign insights.

Leading Change Network

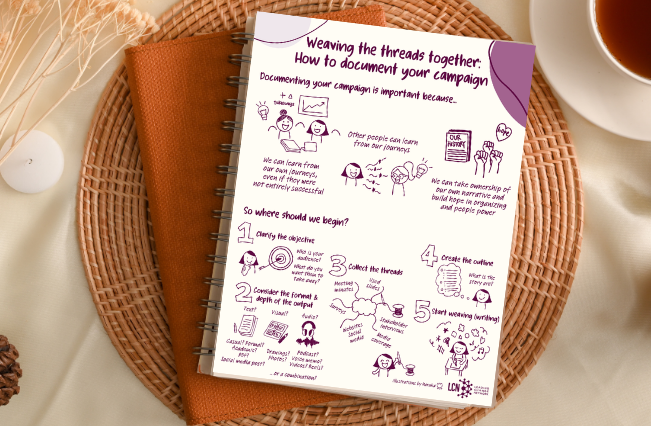

Haruka Sano from LCN outlined a structured approach to documenting campaigns, emphasising the importance of clarity of purpose and audience. She explained that the first step was to identify the objective of the documentation—what it aimed to achieve, who it was for, and what the audience should take away. The format and depth were then chosen accordingly: for example, visual content suited organisers seeking creative tactics, while detailed case studies worked better for trainers teaching campaign strategy.

Next, she described gathering the “threads”—materials such as meeting notes, slides, posts, and interviews with campaign participants—ideally while the campaign was still underway. These threads informed an outline that shaped the story to be told, which was then woven together into a coherent narrative.

The How to Document Campaign Guide supported this process with example questions and templates based on Marshall Ganz’s People Power Change Framework, which included five leadership practices. The guide also provided templates for visioning and case studies, deeper reflection questions and links to additional campaign documentation resources.

Jacob Okumu, Community Organizer, Kenya

Jacob Okumu led a community organizing campaign in Ngong’, Kenya, between 2011 and 2014, aimed at addressing child poverty by keeping children safe and in school. The campaign mobilized over 300 parents and care takers and successfully re-enrolled 1,200 children, while also building a resilient community that collaborated with local government to sustain educational improvements.

Jacob explained that he used the new How to Document Campaign Guide to record the campaign’s journey and that this process helped him reflect on lessons learned. Initially, documentation had not been part of the plan, but the team later realized the importance of capturing their transformational experience—both to inspire others and to show how community organizing could work effectively in East Africa, despite perceptions of it being U.S.-centric.

In documenting the campaign, the team first clarified their objectives—to record the process, lessons, and challenges for other organizers and trainers in the region. They gathered scattered materials such as meeting notes, coaching reflections, social media posts and community forum records, organizing them into a coherent narrative. One major challenge was that key members had moved o, and much of the documentation relied on memory. This highlighted the importance of intentional record-keeping during campaigns to make later documentation easier.

You will need [to tell the story of your campaign] later on. You will need this, even if it’s not for you, then for your community that you lead to inspire, or the change leaders that will come after you. So be intentional as you organize, because that will help you capture the most important information that can help you with the documentation.

– Jacob Okumu

Vijay Sehrawat, Climate Justice Campaigner, India

Vijay Sehrawat reflected on his long-standing passion for documentation, which began in his teenage years when his mother was a campaigner. Revisiting her campaign photos and materials has continued to inspire him, shaping his understanding of how documentation preserves strategy, learning and memory.

He described the Youth for Better Buses campaign in Delhi, led by college students advocating for improved public transport. The campaign built “power with” (community bonding and capacity building), and “power over” (holding politicians accountable). Their efforts led to a policy win, with the Chief Minister announcing 50 new buses for students.

Documentation was integrated throughout the campaign rather than added later. It helped participants see themselves as leaders, strengthen solidarity and reflect on both outcomes and personal growth.

Documentation was not an afterthought in the campaign. It was part of building power. Documentation has helped us see ourselves as leaders, build solidarity, and create public pressure. [It] allowed reflection not just on output, but also for internal growth. The campaign was led by first-time organizers, so it made their leadership visible and valued.

– Vijay Sehrawat

Strategic documentation, such as mapping 40 colleges with poor bus access, guided planning and stakeholder communication. The team also recorded over 800 one-on-one conversations between student organizers and bus users, which supported both real-time learning and future reference. They created podcasts where young people shared personal stories linking the personal to the political, using accessible formats they enjoyed.

A dual leadership model—pairing two leaders for each project—was documented to show how collaboration worked amid students’ competing priorities. Vijay emphasized that documentation itself was a form of organizing, strengthening collective memory and movement power.

I feel documentation itself is organizing, and organizing is intentional. The more you practice the documentation, the stronger movement memory and power will become.

– Vijay Sehrawat

Starting with a Template

Sometimes it’s hard to take that first step to start documenting. So we set aside some time for participants to fill in the visualizing template for documenting our campaign (see page 9 of How to document your campaign guide), which was inspired by a four-frame manga (comic) strip in Japan, using a simple storytelling approach of kishotenketsu (ki: an introduction, sho: development, ten: twist, ketsu: conclusion).

Each frame is an empty box, in which participants can jot down words or draw any scene that comes to mind when thinking about the story they want to tell about their campaigns. Afterward, the participants went into triad breakout rooms to share what they filled and comment on each other’s stories.

As this session was just the beginning of an ongoing conversation for us to discuss our documentation practices and actually document our campaigns, some of the participants committed to meeting regularly in a follow-up space called the Weaving Group.

The Weaving Group

The Weaving Group had our first meeting on October 28th, in which we discussed how specifically we can centralize information and document intentionally while running the campaign, among other topics. We shared the common challenge: We ourselves understand the importance of documentation but then how can we engage others running the campaign on the ground to also understand its importance and document their stories on their own? If you are interested in joining this discussion space, please reach out to haruka.sano@leadingchangenetwork.org. Let’s continue discussing the importance of documenting campaigns, share creative tips with each other, and hold each other accountable to actually document our campaigns.

Recording (available for LCN members)

Recordings of the session is available for LCN members here.

If you are interested in becoming a member to watch the recording and access 400+ other resources on organizing – guides in various languages and case studies from around the world – please let us know at resources@leadingchangenetwork.org!

About speakers

Antje Dun

Antje Dun is the Librarian at the Commons Library. Antje maintains the library, creates and adds new content, supervises volunteers, does graphic design and contributes her information management expertise to special projects.

She has worked in many specialist libraries and is also a graphic designer.

Holly Hammond

Holly Hammond is the Director of the Commons Library. Holly directs the Commons Library: developing and implementing strategy, overseeing library operations, tracking social movement needs, forging project partnerships and building the financial sustainability of the organisation. She is one of Australia’s foremost activist educators.

Haruka Sano

Haruka Sano is a community organizer and a trainer based in Kamakura, Japan. She leads the Climate Organizer Program (KIKOOP) at Community Organizing Japan, designing trainings that enable participants to find their people, build teams, and launch campaigns. At LCN, Haruka is the Resource Center Lead, taking care of 400+ resources on the Resource Center, including workshop guides, public narrative videos, and case studies. Working towards a more accessible, diverse, and member-led Resource Center this year, she is thrilled to meet a community of organizers who document and share their campaigns and learning together.

Vijay Sehrawat

Vijay Sehrawat (he/him) is a documentary filmmaker and climate justice campaigner based in New Delhi, India. He is the co-founder of Youth For Climate India (YFCI), a community of 15,000 young people campaigning across 100+ cities on issues such as air pollution, public transportation, climate education, and green public spaces. Vijay is also the co-founder of the Climate Justice Library, the first climate justice library in Asia, which aims to make climate literature and literacy accessible to communities. Currently, he is building the Young Feminist Resource Hub, a space dedicated to supporting young feminist organizers with knowledge, tools, and resources. He also coordinates the Young Founders Network, a peer-led network of 12 young founders who support each other in navigating leadership, sustainability, and organizational growth in the social and climate justice space.

Jacob Okumu

Jacob Okumu, based in Kenya, is a teacher by experience, a project manager and a community organizer with knowledge and experience in training, coaching, designing, and managing people centric projects/campaigns for social change. He is a supporting coordinator at Global Grassroots Support Network. He has led and managed campaigns and projects with organizations such as Be the Change Kenya, Tatua Kenya, Amnesty International Kenya, UNICEF Tanzania and Change.Org where he has been infusing digital and offline campaign strategies to enable petitioners and Change Leaders accelerate change as a campaign strategist. He is a member of the Young African Leadership Institute (YALI) Alumni, and Leading Change Network. He is passionate about justice and equality.

People, Power, Change framework

Learn more about the People, Power, Change framework here:

Resource Information

- Year: 2025

- Author: Antje Dun, Haruka Sano

- Tags: —

- Access : Public

- Regions : Global

Back to search results

Back to search results